France in the Middle Ages 987-1460: From Hugh Capet to Joan of Arc by Georges Duby; translated by Juliet Vale.(Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.) 1991.

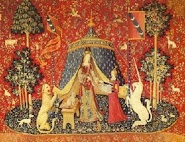

This volume by Georges Duby (1919-1996), distinguished professor emeritus of the Collège de France, was written about ten years before his death. It is an excellent resource and a good introduction to French medieval history for the serious student of French history. His argument is especially strong in connecting the evolving French political, economic, and intellectual movements to counter-developments in historic events and thought. It is part of a larger series on French history that was commissioned to celebrate the Millennium, and his section, despite its title, is a short introduction that introduces his real expertise in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries, with a short wrap-up of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The choice of Joan of Arc to represent the single even of the fifteenth century is mean to connect to the next volume (written by Leroy Ladurie) and to demonstrate the continuing romantic influence of the symbolism of the Middle Ages—especially through adaptation of sacred symbols to modern and secular movements and national allegiance.

While he is primarily interested in social history, especially as it pertains to tracing the development of feudalism, he appeals to younger historians to write feminist history, gently offering questions and direction for further study. He is sensitive to the plight of women, as comments in his book, The Knight, The Priest, and The Lady, based on very popular public lectures he delivered in the 1980’s at the College de France had demonstrated. In later years, Duby limited the focus of his writing (he also continued to direct a center for medieval studies in Provence) to the narrative history he had pioneered with Leroy Ladurie and others, preferring to offer his own views and interpretations, based upon a long and successful career.

French scholarship applauds his writing--he was, after all, a member of the College de France. But some English-language peer reviews, while acknowledging his legendary historical reputation, criticized his decision to decline construction of a feminine narrative, citing a lack of documentary evidence for the tenth through thirteenth centuries in France, and admitting the lethargy of the French academy’s attention to feminist history. He noted that he felt unqualified to speak for these hypothetical women, as neither his training nor his gender qualified him to do so. I found his reluctance charming, and consistent with the polite manner of a gentleman of his generation. One female historian, no doubt aggrieved over the impossibility of finding substantive support in Duby’s scholarship for feminist history projects, wrote that she was “angry” that he had died before replying to her review of his work! Some English-speaking historians seem to have declared that every work must explore every issue from every possible viewpoint in order to meet peer approval standards, a demand that has led to a great deal of sameness and dreary redundancy in current academic work.

In this volume, Duby produced a brief summary of the study and conclusions he reached in a lifetime of careful research, presented with a soupcon of the distinctive and compelling narrative style of the Annales historical method, which he helped to pioneer. Duby’s style will not please modernists, who offer deliberately bland, disinterested voices that confer objective authority, while asking us, like the Wizard of Oz, to ignore the actual men and women behind their disembodied voices. By contrast, Duby's historical narrative voice is lively, engaging, intelligent, humble, and authoritative. I like his voice, so I enjoyed the book. Overall, the book is one which would stimulate discussion and cause serious students to want to inquire further, while providing excellent insights from an important French historian.