Plus que Jamais--a favorite perfume from Guerlain of Paris, a gift from my daughter and souvenir of our marvelous summer vacation together in Paris.

Plus que Jamais--a favorite perfume from Guerlain of Paris, a gift from my daughter and souvenir of our marvelous summer vacation together in Paris.It means longer than never--forever--much longer, in fact, than the very old French history I study. The name describes much of who I am and why I love history.

History is like a perfume, in many ways, with hints and scents of long ago times and far away places. It lingers in the memory, tantalizing the senses and imagination, like the aroma of cedar in old trunks, the mustiness of old books, the oaken scent of library shelves and tables, or a faint spiciness of old cupboards.

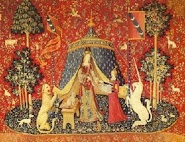

As a child of the twentieth century, who lived (the French would use the verb demeurer--our now, alas, "archaic" word in English--dwelt) most of her childhood in the nineteenth century Romantic revival of the Medieval era, immersed in the art and literature of Howard Pyle, Alexander Dumas, Sir Walter Scott, and others, I developed a determined taste for pre-Raphaelite painting and Romantic poets.

Like Anne Shirley of Anne of Green Gables renown, I love the "scope for the imagination," which the study of history affords me. My friends love their literature studies, and probably share much more common ground with my old lights of the Victorian Romantic era, but I love history's cranky old modernists, its Annales factoids, with their tendency to produce woolly narrative histories in their dotage. They are my Victorian fantasy of the the tweedy old professor with suede elbow patches, smelling faintly of pipe tobacco, tea, and whisky, enveloped by book-lined library walls, ensconced in a worn leather armchair. I've loved this gentleman since my youth, although I have never actually met him! History has a lingering masculine quality about it that gender historians sometimes deplore, while I am drawn by it.

French History? Well, you'd have to attend Evergreen to understand. The best liberal arts program for my interests combines study of French history, culture, and language. But, knowledge is power--or if I'd had the privilege of Latin grammar school--scientia est potentia-- so it must be good for something. My history professor is young, knowledgeable and challenging, while the literature/art history/philosophy professor is a woman "of a certain age," like myself, with an approach that is uniquely her own, and rather European. Both these amazing women have their own structured approach to teaching and life, as well as being wonderful women who inspire their students and teach their beloved subjects with love and formidable intelligence.

Now I'm reading early modern history--lots of mud, plague, and Huguenots--looking for that twist of interest that will grab my imagination and take it in the direction of a good question. I loved writing about Catholic women's reaction to the dechristianization program of post-Revolutionary France. Next I enjoyed looking at the rise of the department store and its effect on women's lives, as well as the role of fashion as an indirect area of expression and influence that reflected women's broadening roles and attitudes in the modern era, providing an ambiguous, yet public, force in the marketplace long before Frenchwomen actually achieved the right to vote.

Ankle-deep merde of the early moderns, I can't hear much rustling silk or sharp wit among the common folk, although I believe France was once famous for its silks and the Lyon silk merchants became quite wealthy. (I remember that France was the ribbon capital of Europe--can't remember where they made them--Amiens, perhaps?)

.gif) An immense distance separated the wealthy courtiers of Louis XIV, or even the XIII, and the common cloth of French peasantry--their poverty, illiteracy, disease, and superstitions. In their own time, the wealthy barely thought of the poor as human beings, perhaps much like our own homeless, whose ragged, wretched appearance, and lack of direction may cause more fortunate members of society to view their lives as meaningless. At the same time, society's religious views deemed that charity toward the poor was a virtue, thus many acts of individual and institutional benevolence provided a some relief. Then, as now, its palliative effect was hopelessly inadequate to the enormity of the problem, and could never significantly alter the great gulf between rich and poor. Thus, we know very little about them.

An immense distance separated the wealthy courtiers of Louis XIV, or even the XIII, and the common cloth of French peasantry--their poverty, illiteracy, disease, and superstitions. In their own time, the wealthy barely thought of the poor as human beings, perhaps much like our own homeless, whose ragged, wretched appearance, and lack of direction may cause more fortunate members of society to view their lives as meaningless. At the same time, society's religious views deemed that charity toward the poor was a virtue, thus many acts of individual and institutional benevolence provided a some relief. Then, as now, its palliative effect was hopelessly inadequate to the enormity of the problem, and could never significantly alter the great gulf between rich and poor. Thus, we know very little about them.It seems to me that most historians begin their discussion of early modern history by remarking that we cannot hope to think we could understand the people of earlier centuries and are mistaken if we think they are like us. So far, nearly every historian I have read has begun with a statement that reflects a sort of metanarrative that the people of a few hundred years ago are so different from us that we cannot expect them to be comprehensible to us. My question for all these authors is: If we cannot understand or expect these people to think and behave with comprehensible human feeling, thought, motives, and beliefs, then would not that assumption affect all our subsequent analysis of their history? To begin by saying we cannot understand people who are clearly of the same species as ourselves is to begin with a seriously flawed historical outlook.

Perhaps this perspective has its origins in the progressive view of history that supposes that mankind is becoming more civilized with the passage of time and thus far removed from its primitive origins. Obvious objections to such a view as a privileged and erroneous view of history begin with its clear implication of civilization as a primarily Western venture,

with all other cultures relegated to some measure of primitive evolutionary substrata. Additionally, even in our own Western culture, it could be readily admitted that our great geniuses of history appear to have been much more productive and creative in shorter lifetimes, with far fewer tools to support their work, than our far more numerous modern minds, equipped with computers, long lives of leisure, and knowledge of the ages at our fingertips. Furthermore, one can scarcely judge the vileness of earlier criminal classes or the brutality of distant ages to be effectively worse than our own, simply by their closer proximity to everyday danger and violence. Our prisons, military, police, and institutions shield many of us from individual participation in executions, war, torture, and other unpleasant violent realities. Our distance from the processes of birth and death, and our greater privacy does not support the conclusion that we are more civilized. Cruelty, ignorance, vice, corruption, envy, malice, greed, lust for power, and murder continue to destroy humanity, along with the problems of war, plague, and poverty.

with all other cultures relegated to some measure of primitive evolutionary substrata. Additionally, even in our own Western culture, it could be readily admitted that our great geniuses of history appear to have been much more productive and creative in shorter lifetimes, with far fewer tools to support their work, than our far more numerous modern minds, equipped with computers, long lives of leisure, and knowledge of the ages at our fingertips. Furthermore, one can scarcely judge the vileness of earlier criminal classes or the brutality of distant ages to be effectively worse than our own, simply by their closer proximity to everyday danger and violence. Our prisons, military, police, and institutions shield many of us from individual participation in executions, war, torture, and other unpleasant violent realities. Our distance from the processes of birth and death, and our greater privacy does not support the conclusion that we are more civilized. Cruelty, ignorance, vice, corruption, envy, malice, greed, lust for power, and murder continue to destroy humanity, along with the problems of war, plague, and poverty.Of course, most historians, despite their underlying belief in the alien character of the non-modern mind, proceed to attempt to understand them. Perhaps most historians only dismiss the mass of humanity, not its geniuses and nobility and leaders, with whom they presumably share a common understanding, for they often speak quite confidently about the thoughts,

habits, behavior, and motives of elite historical individuals. The device of claiming that earlier centuries did not understand the world in the same way as modern people is perhaps to excuse our lack of information about them, but it is primarily rooted in the natural distaste of the comfortable, rational, and well-fed for the desperately poor, struggling, superstitious, and starving mass of humanity. Foucault would say that unreason is always in retreat from reason, but I am sure that the reverse is also true. Orderly educated minds shrink from the mass of disordered humanity.

habits, behavior, and motives of elite historical individuals. The device of claiming that earlier centuries did not understand the world in the same way as modern people is perhaps to excuse our lack of information about them, but it is primarily rooted in the natural distaste of the comfortable, rational, and well-fed for the desperately poor, struggling, superstitious, and starving mass of humanity. Foucault would say that unreason is always in retreat from reason, but I am sure that the reverse is also true. Orderly educated minds shrink from the mass of disordered humanity.I would like to remind myself to begin any examination of history with the certainty that humanity is and has always been humankind. Thus, historical people must be seen as sentient beings, like ourselves, but with the problems and perspectives of their own time and circumstances. To do otherwise is to render any study of history an arcane pursuit of facts and events which we cannot hope to comprehend or relate to our knowledge of human nature. Particularly, in the early modern period it is necessary, from my own belief in the constancy of human nature, to embrace the humanity of the wretched creatures who comprise a world where often ninety percent of the people are hungry and only ten percent are adequately fed. It is a fundamental principle that would serve well for approaching both our past and our present time.