This night for to ride

The Devil and she together

Through thick, and through thin,

Now out and then in,

Though ne’er so foul be the weather.

A Thorn or a Burr

She takes for a Spur;

With a lash of a Bramble she rides now,

Through Brakes and thorough Briars,

O’er Ditches and Mires,

She follows the Spirit that guides now.

No Beast, for his food,

Dares now range the wood;

But hushed in his lair he lies lurking;

While mischiefs, by these,

On land and on Seas,

At noon of Night are a working.

The storm will arise,

And trouble the skies;

This night, and more for the wonder

The ghost from the Tomb

Affrighted shall come,

Called out by the clap of Thunder.

Robert Herrick

Talking with my younger daughter yesterday, we laughed at the irony of our church's choice this year, of a Celtic-themed "Harvest Party." While I'm an unabashed Celtic enthusiast--although a full-flown Druid Samhain celebration, complete with burning human sacrifices in wicker baskets goes too far for me--this announcement surprised and amused me, remembering how Harry Potter got such condemnation at this same church more than a decade ago.

The church’s high school had once officially reprimanded my (then) 15-year-old daughter for attempting to show the first Harry Potter video in an empty classroom during lunch, to a group of curious students who wanted to judge the so-called ‘witchcraft’ controversy for themselves. Now, being educated Presbyterians, the school and church deemed C.S. Lewis’ Lion, Witch, and Wardrobe, and Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings, with its sorcerers and such, to be near-sacred works of Christian literature. My daughter felt that Harry Potter books were unfairly stigmatized, while fairy tales and folk tales, or even works such as The Wizard of Oz, with no Christian pretensions whatsoever, received no such proscription. Her forays into freedom of intellectual inquiry were frowned upon at Covenant High, however, so this year’s Celtic theme provoked much mirth and hilarity!I had long fantasized about appearing at one of these Harvest Parties as one of Macbeth's witches to quote some favorite lines, cavort a bit naughtily, mumble curses and even, perhaps, foretell a bleak future to a self-righteous authority figure or two--but now my mind ran to Druid priestesses and wicker baskets. Surely, this was not the intent of the theme, but an unchained imagination with an eye to mischief could be expected to revel a bit in such fantastic possibilities!

I still wonder that Protestant churches, having long given up most of the church calendar and having lost sight of the historical connection of church holy days with pagan festivals, criticize syncretism in the Catholic Church, while remaining reticent to connect their own need to provide celebrations for their adherents that replace pre-Christian and modern cultural festivities with church observances. The liturgical calendar celebrates All-Hallows' Eve (first given official recognition by Benedictines in 998, and receiving Papal approval in 1006), with remembrances of the dead and masses for the following All Saints' Day. Since that time, irrepressible folk customs rooted in pre-Christian beliefs have persisted in our cultural celebrations, despite church efforts to subdue them.

All-Saints' Day was a full-blown celebration of the redeemed dead, and one of the most important days in the church calendar, as it followed and was meant to distract from and replace the ancient pagan festival of Samhain. It marked a redemptive light after the dark day of the dead--a kind of resurrection of the dead in Christ--and the full circle from Easter, as the dead in Christ rise as he is the first to rise in the Spring. Syncretism? Of course. We are creatures of earth and seasons. Some festivals of the Old Testament even provided similar seasonal cycles for the desert-dwelling Semitic tribes of Israel, notably, the feasts of First Fruits, Trumpets, and Tabernacles.

Nevertheless, I will refrain from posing as a hag to frighten the faithful at their Celtic harvest coven (a fine Medieval Scots word originally used for any gathering!) But I will remember them with a smile while I pass out treats to the wandering goblins, princesses, and pirates who are my neighborhood children. While their trick-or-treating may not be nearly as darkly authentic as my lamb stew-eating and pumpkin-carving Presbyterian clan, who celebrate Harvest with themes of blood-drenched Reformation and pagan conquest--which as a Reformation historian I can thoroughly appreciate--I will enjoy the irony of their embrace of syncretism, however much they doth protest! I will even forgive them for fearing that my daughter might corrupt their children with her cherished Harry Potter film. To her great delight, Shakespeare nevertheless figured prominently in her high school literature classes, including class performances of Macbeth with enthusiastic witches, (albeit bowdlerized of most age-inappropriate sexual gyrations and lines). With all that Celtic influence, I suspect they will have a great harvest party to remember, and I will not remind them what fun a little paganism can provide!

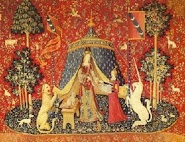

I hope the moon is full and the night dark with mere wisps of clouds. Robert Herrick, poet of hymn-writing fame, combined pagan themes of Samhain with Christian themes of death and resurrection in "The Hag." I will look at the night sky on this All-Hallows' Eve, and hope to catch a flash of broomstick across the moon.

.gif)